I’ve been working with a small database of national wealth estimates circa 1913. There are only twelve countries in it, but, crucially, it includes the only two that really matter. I’m referring, of course, to the (possibly apocryphal) line from Simon Kuznets. “There are four kinds of countries: developed countries, developing countries, Japan and Argentina,” he is supposed to have said.

To see why Argentina and Japan stand out, it is helpful to compare the wealth per capita of my twelve countries circa 1913 with their wealth per capita a little over a hundred years later, in 2018, according to the World Bank’s estimates. The coefficient of determination (R2) was just 0.33, meaning that being wealthy in 1913 was a poor predictor of being wealthy in 2018. With Argentina and Japan excluded from the sample, however, the R2 increases to 0.75. That’s why they are the only two interesting countries, at least when it comes to explaining (under)development in the twentieth century.

The reversal of fortune between Argentina and Japan was profound. Circa 1913, the average Argentine was worth about £280, whereas the average Japanese was worth £50. Yet by 2018, the average Japanese was worth $257,000 and the average Argentine $50,000. They had switched statuses as “developed” and “developing” countries—that’s what Kuznets meant.

But a hint of why this reversal occurred could already be seen early in the twentieth century. Despite its relative poverty, Japan was already better at government than Argentina. For me, probably the clearest indication comes from primary school enrollment. According to Aaron Benavot and Phyllis Riddle’s database, the Japanese government was able to get 59 percent of its young children into school in 1910; in Argentina, by contrast, only 37 percent attended. Despite its country’s wealth, the Argentine government was already failing to provide the kind of public goods that were important for growth in the twentieth century.

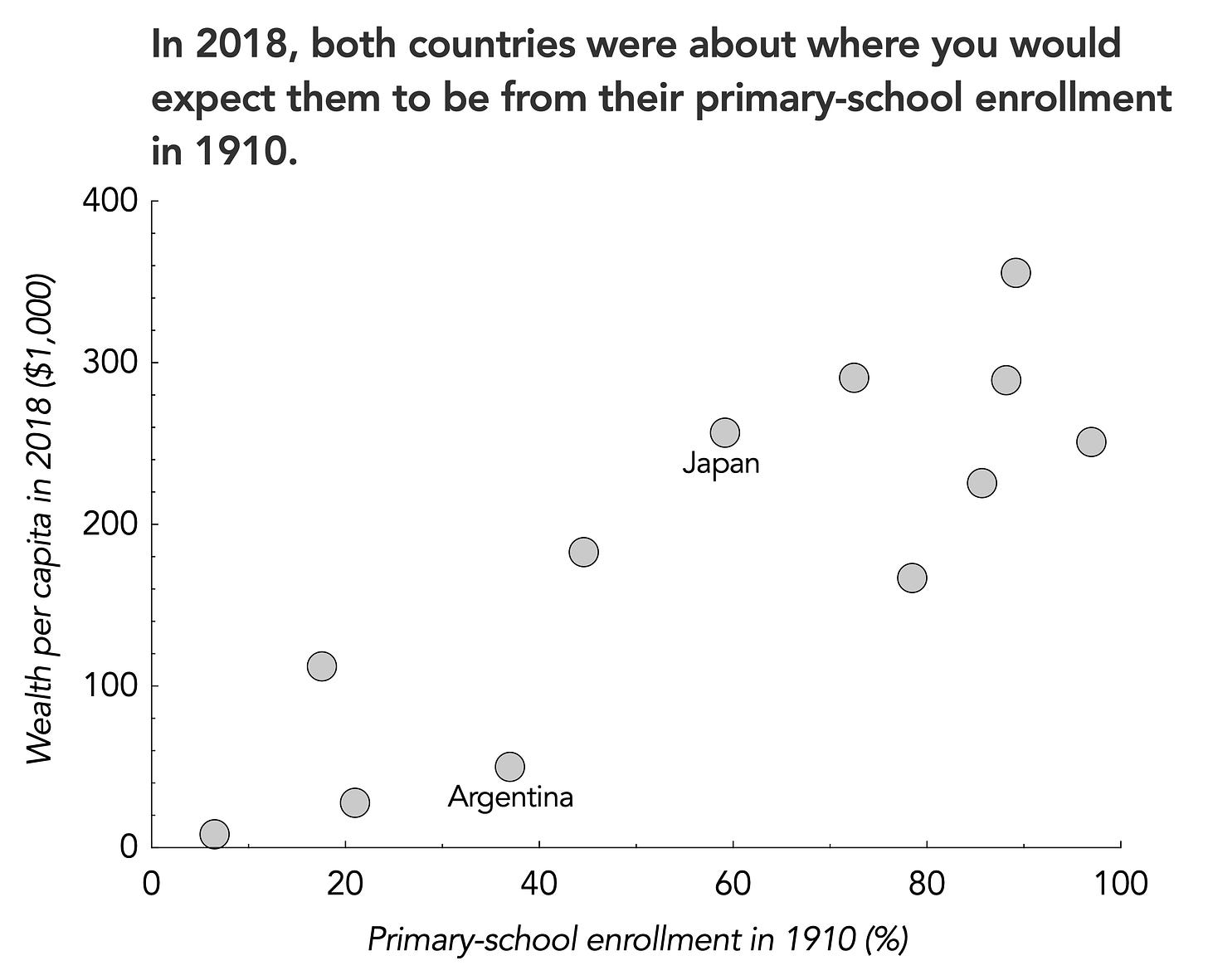

With hindsight, the distinct trajectories taken by Argentina and Japan were somewhat predictable. Looking again at the sample of twelve countries, the two countries’ levels of wealth per capita in 2018 were about where they should have been according to the level of primary school enrollment in 1910. For the twelve countries, the R2 of the two variables is 0.74. When a broader sample of 65 countries is used, it falls somewhat, but remains quite high at 0.53—over half of the variation in the countries’ wealth per capita in 2018 can, in statistical terms, be explained by the level of primary-school enrollment in 1910.

The major caveat to this is that it is all in hindsight. As a historian, I can see that land abundance was the key to making Argentina wealthy by 1913. For twentieth-century Japan, on the other hand, government was vital. But that does not mean that government will necessarily have the same importance for growth and development in the twenty-first century. For this reason, some skepticism is warranted when people use the Argentinas and Japans of the world to sell political projects in the present. The past is not always a reliable guide to the future.

I am an independent scholar, so my opportunities for funding are limited. Any donation you can make to help me write The Poor Rich Nation would be fantastic.

Dear Mr. Francis,

Quality work, very interested post and very close to my field of research. You may find some useful informations in my book "Ideas, burocracia e Industrialización en Argentina y Brasil" (https://www.lenguajeclaro.com/etiqueta-producto/perissinotto/). In the last chapter I extend the comparison to seven other countries, Japan included. The same book was also published in portuguese, when some typos were corrected (https://eduerj.com/produto/ideias-burocracia-e-industrializacao-no-brasil-e-na-argentina/). Best regards.