When nominal beats purchasing power parity

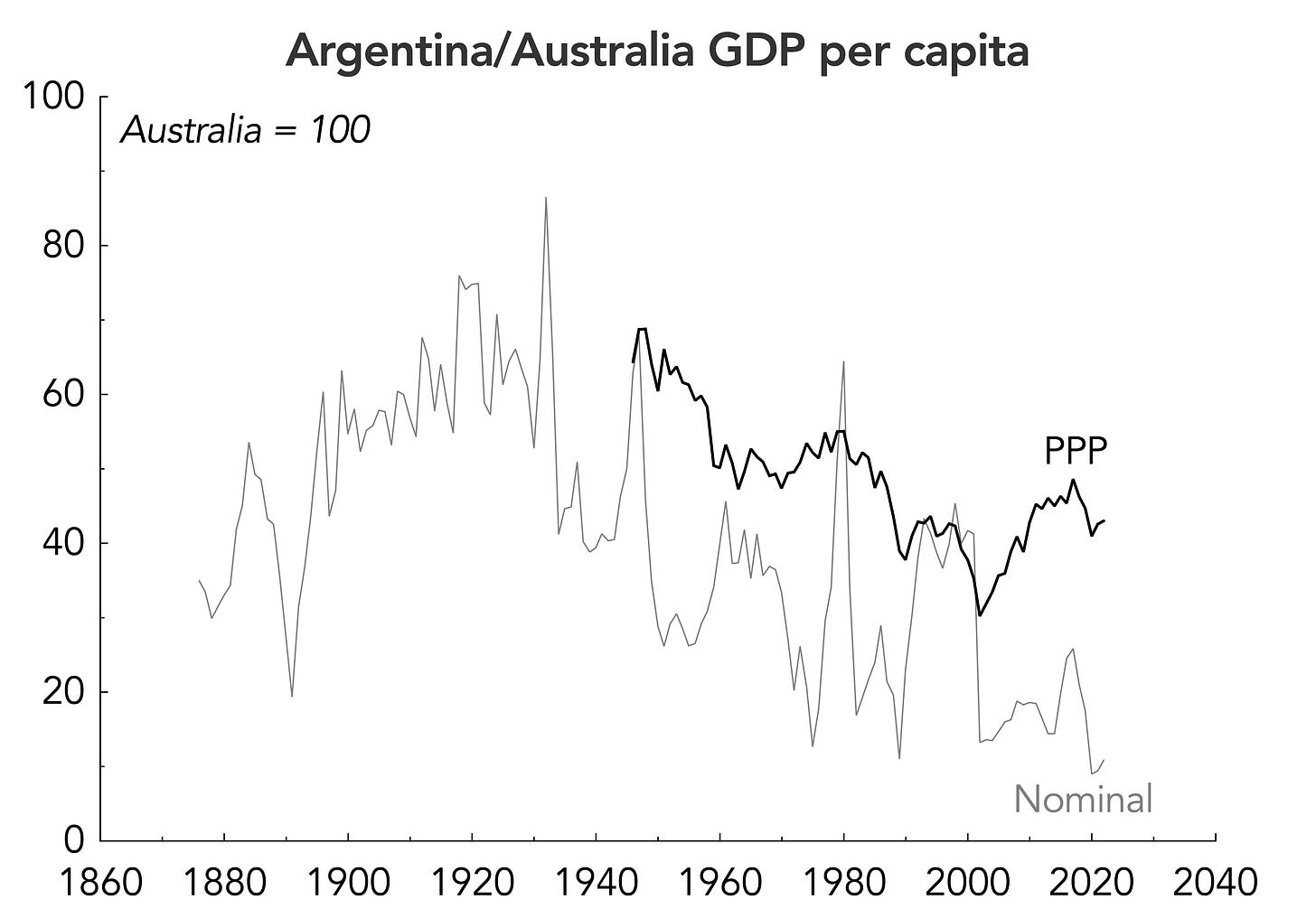

Looking at Argentina’s relative nominal GDP per capita gives a clearer indication of when its decline began

Economists like to adjust GDP statistics for purchasing power parity (PPP) because it gives an indication of the relative levels of welfare between two countries. There is a case to be made, however, for using nominal measures that have not been adjusted for prices.

Giovanni Arrighi, for example, explained why he preferred to use estimates of nominal gross national product (GNP) to compare countries: it provided “is an indicator of—and a better indicator than anything else that is readily available—is the command of the inhabitants of the region or jurisdiction to which it refers over the human and natural resources of the organic core, relative to the command of the inhabitants of the organic core over the human and natural resources of that region or jurisdiction.” Rather than comparative levels of welfare, then, nominal ratios give an indication of the power of the inhabitants of one country over the another. They therefore say something different to PPP measures, but they are arguably more important.

There is, moreover, a practical reason for an economic historian to use nominal measures of income because it results in one less source of potential error. Estimating historical GDP is already difficult enough, without having to then adjust it for differences in price levels using data that don’t really exist… This is what I have been doing with Argentina’s historical statistics, but I have found that the results are very sensitive to which price-level data I use. Sticking to nominal ratios therefore seems somewhat more objective.

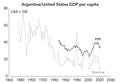

On top of that, in the long term, there does tend to be a correlation between nominal GDP and PPP GDP in the long run. This, for example, is Argentina relative to the United States:

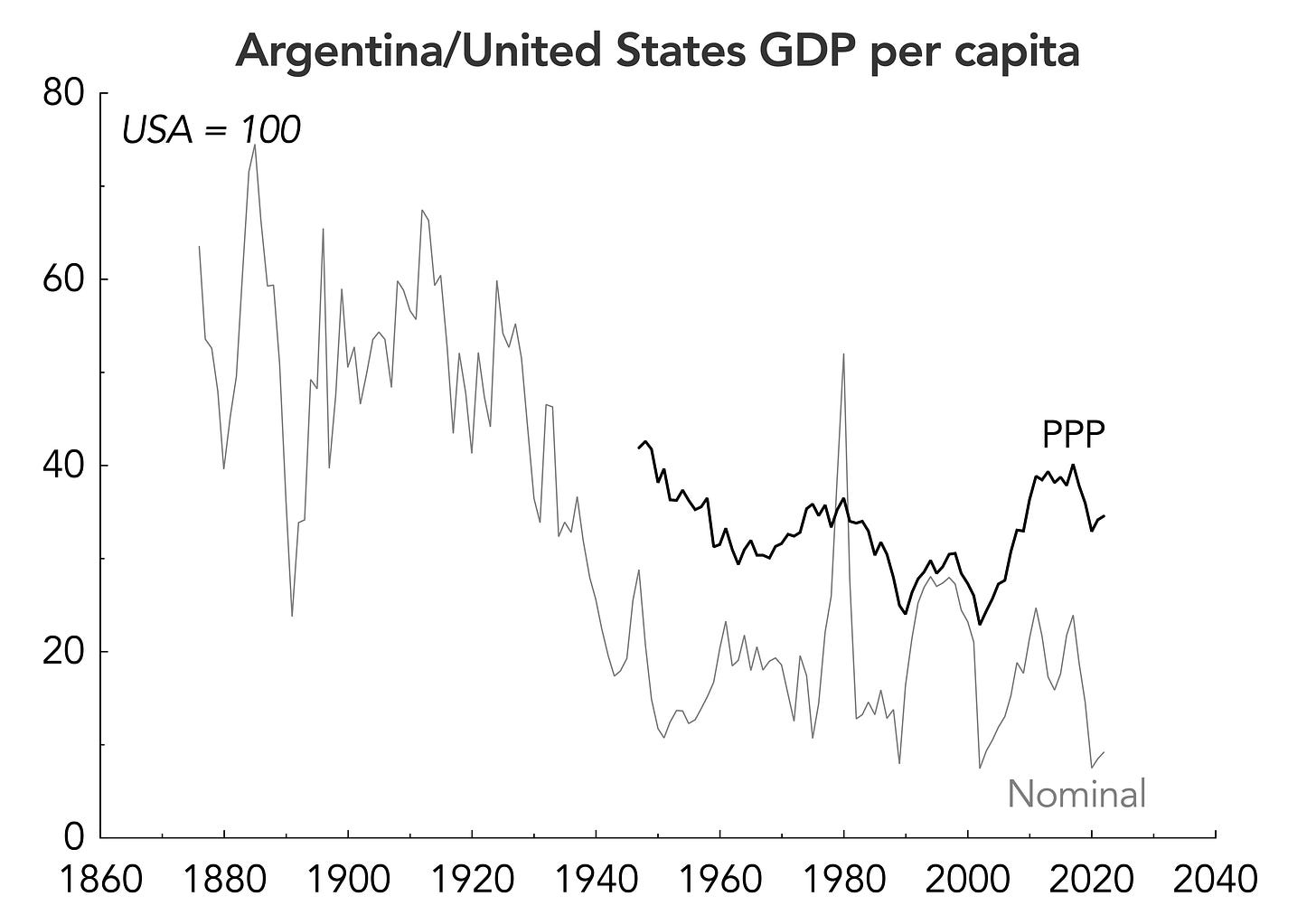

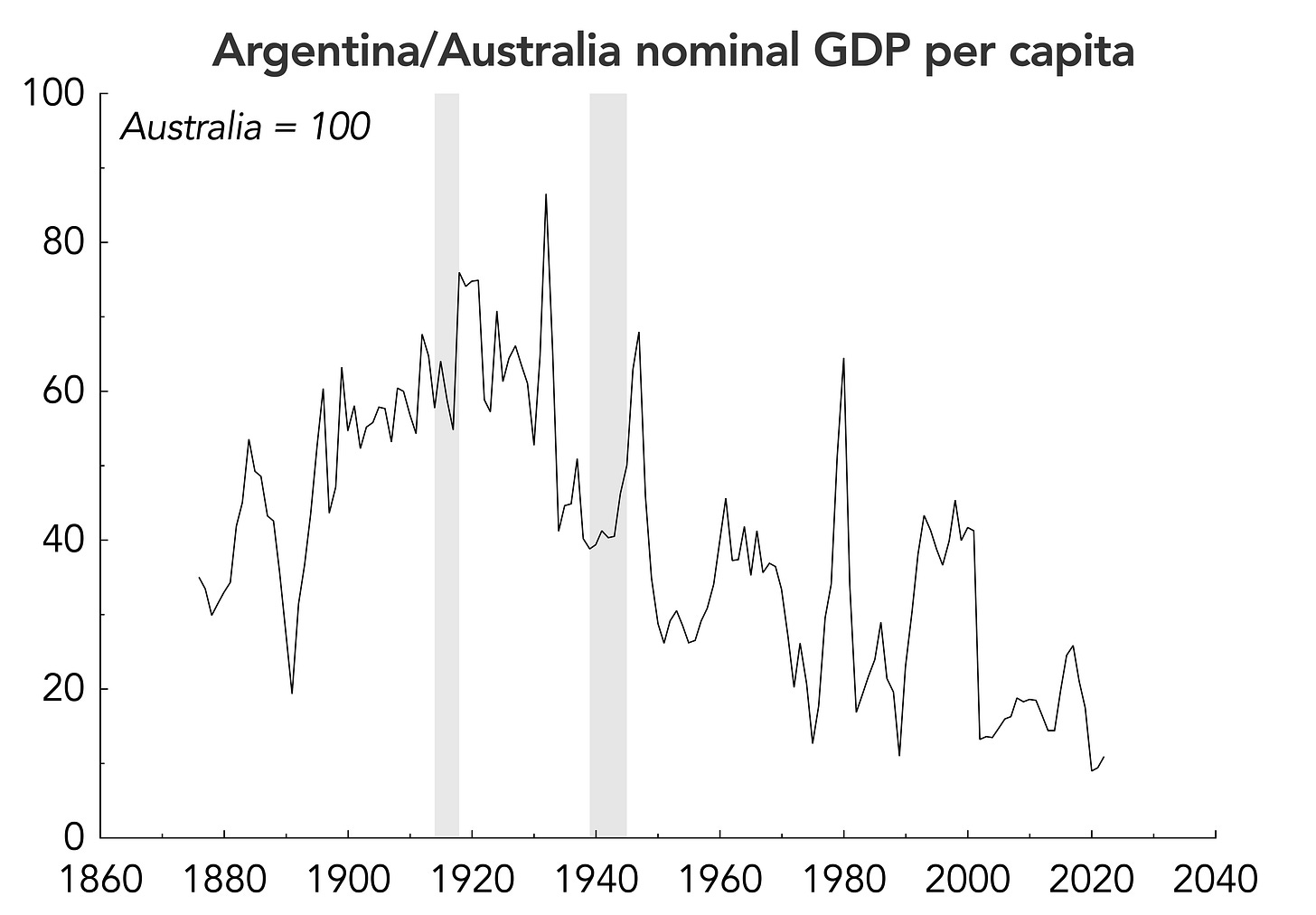

And relative to Australia:

The nominal estimates are based on the free market exchange rate, while I’ve used Colin Clark’s estimates of the price level for 1946 and thereafter various estimates by international organizations for the PPP estimates. My educated guess is that Argentina’s price level was closer to the US and Australia pre-WWI, so the decline in relative PPP GDP per capita was less pronounced than suggested by the nominal series. I am, however, more interested in the timing than the level of the decline, and it’s here that the nominal series are really important.

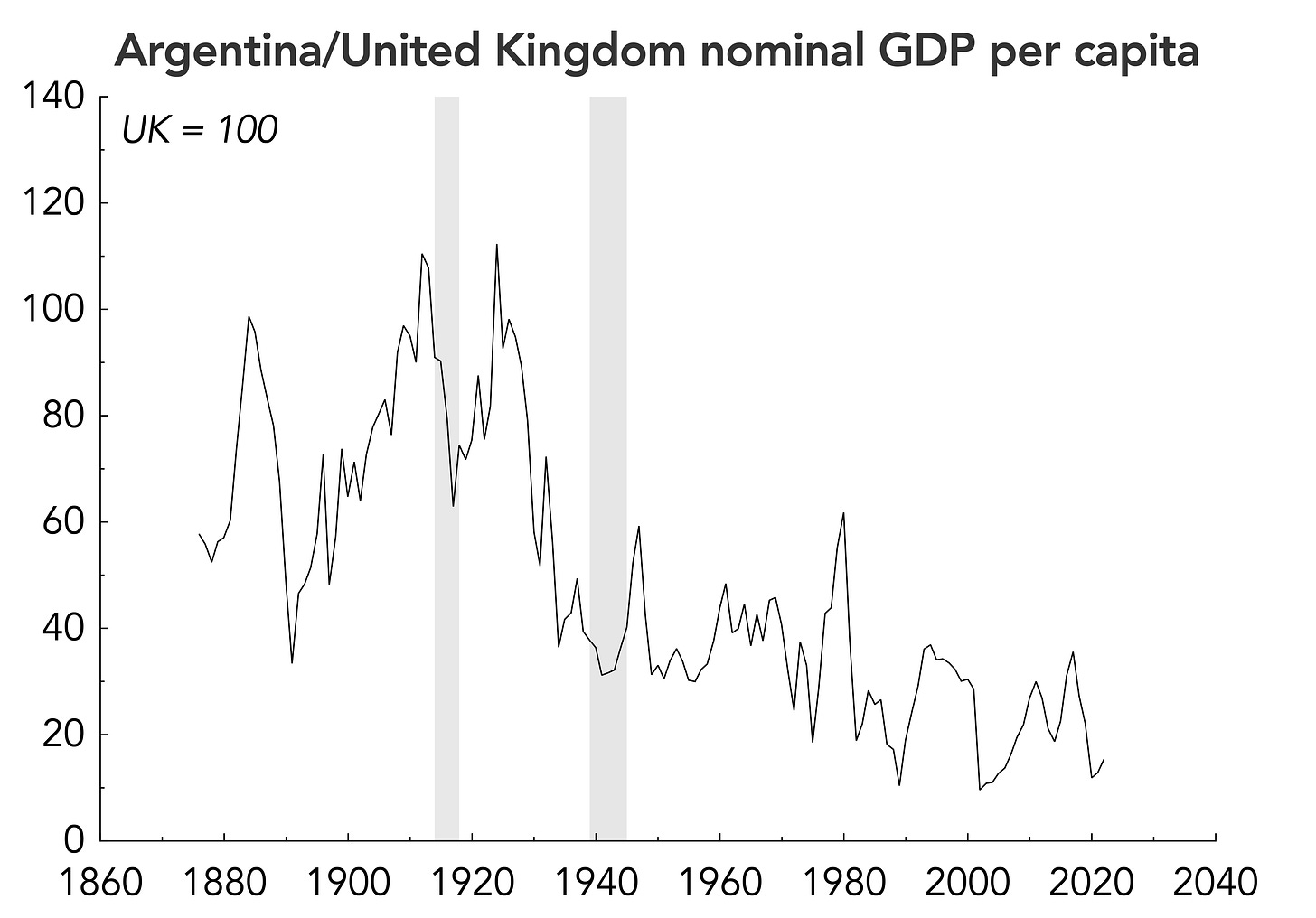

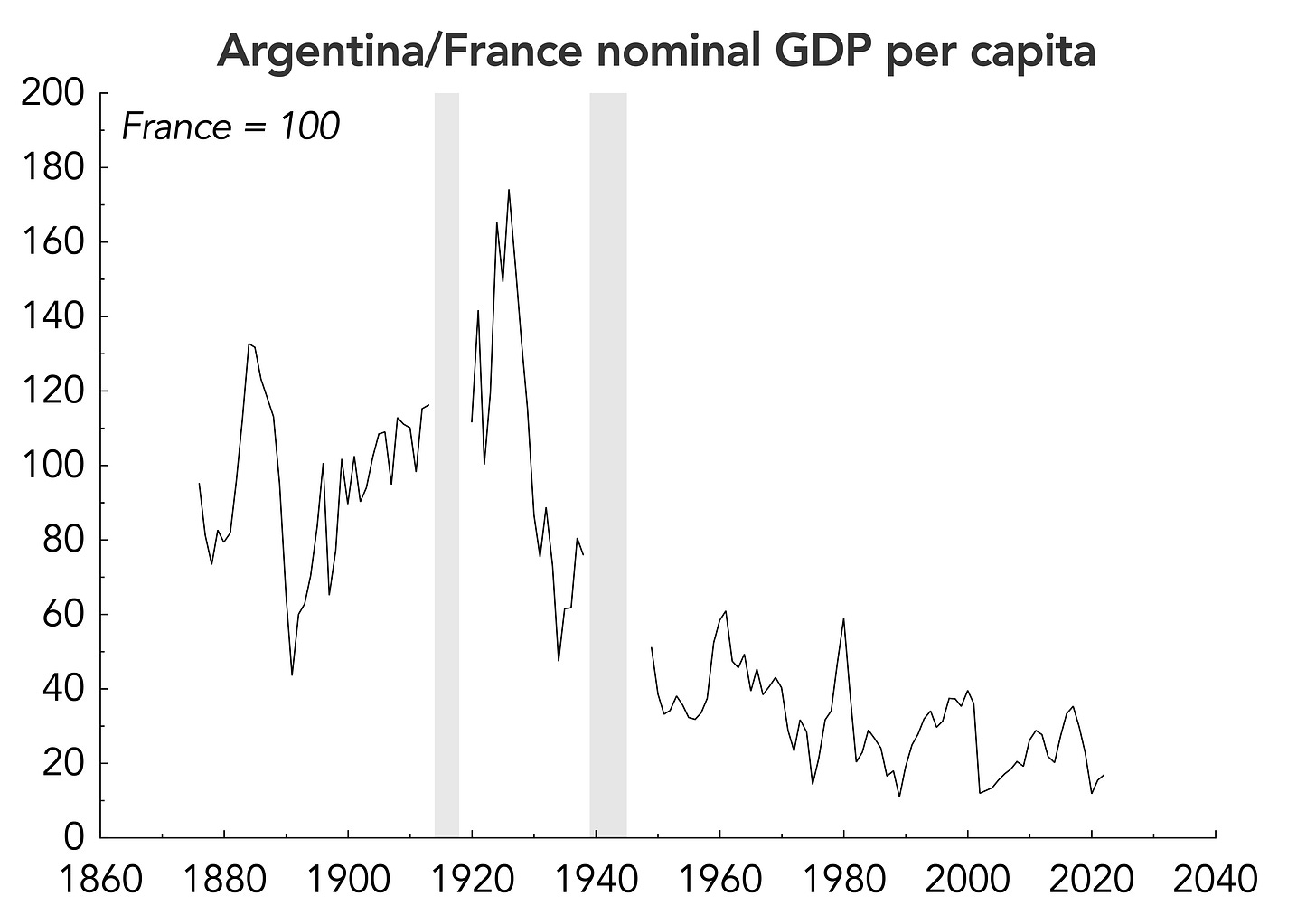

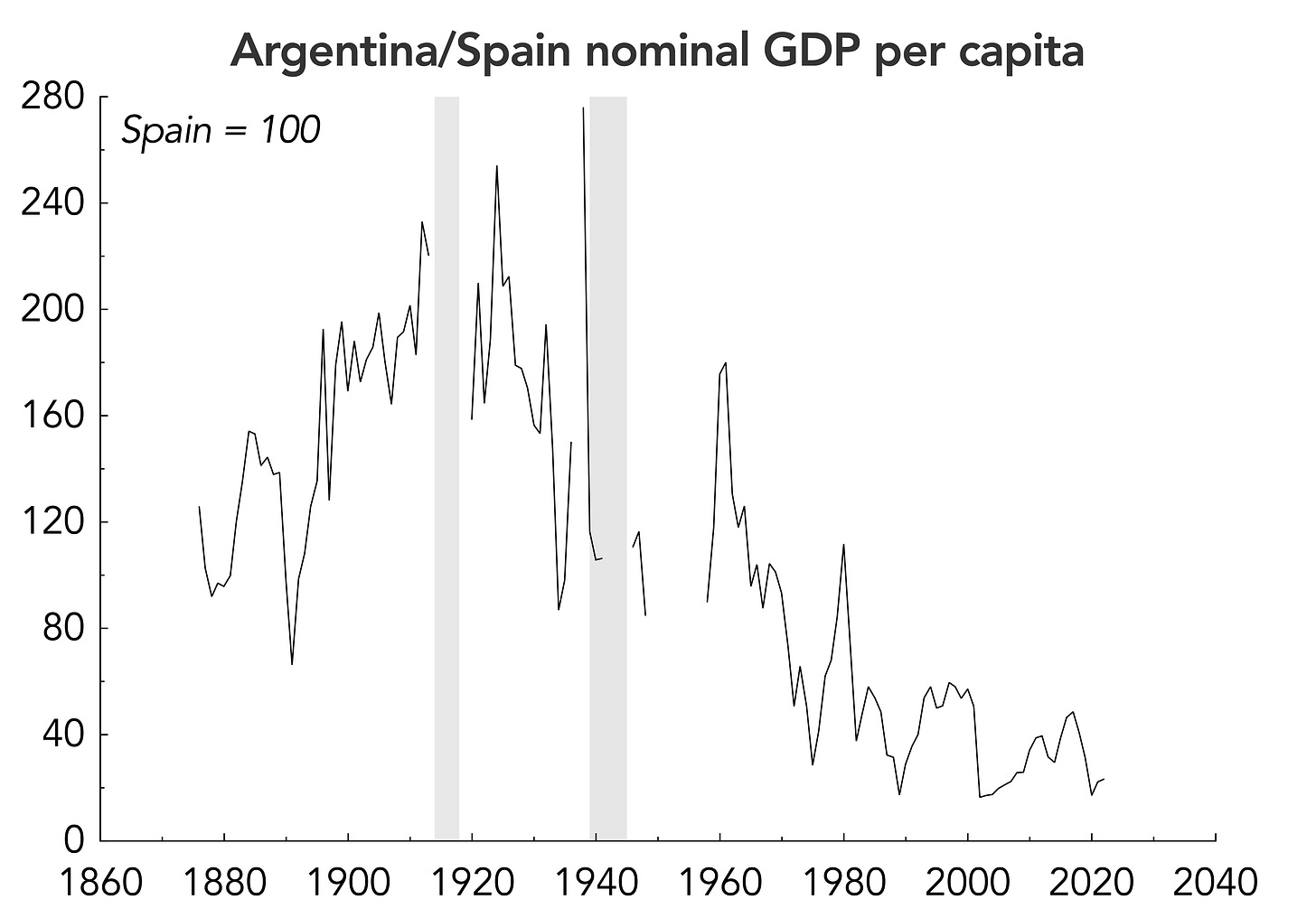

I’m now working on the nominal GDP statistics of various countries. I’m trying to correct for the splicing problem identified by Leandro Prados de la Escosura, which means that existing series tend to overestimate past levels of nominal GDP, especially for developing countries undergoing structural transformation. These are the comparisons that I have been able to make so far:

The series are noisy due to short-term movements in exchange rates, but all point toward World War I and the interwar period as when Argentina’s relative decline began. There were several developments in these years:

Argentina’s frontier reached it limits, as there was little more Pampean land to be brought into production.

The terms-of-trade boom ended, first due to increased transportation costs during World War I, then as a result of the disintegration of the world market for agricultural products during the 1930s, when governments in Europe and North America began to subsidize their farmers.

Argentina’s democratization was interrupted by the military of 1930, which led to an “infamous decade” in which the country’s traditional political class used electoral fraud to maintain its power.

In 1932, the federal government began to print money to purchase its own bonds—a practise that would become institutionalized, driving the high rates of inflation that would become the norm in the second half of the twentieth century.

There are, then, good reasons for there to have been a structural break in Argentina’s development from 1914 to 1945. Perón then emerged as a symptom of decline.

The question is then whether Peronism and anti-Peronism made the decline worse in “positive feedback loop”. Intuitively, it seems likely that Argentina’s more or less violent swings from populism to liberalism and back again can’t have been good for the country. Maybe such instability was bad instead itself, as I previously suggested in the comparison with New Zealand. On the other hand, it might also have meant that Argentina couldn’t exploit some of the advantages that New Zealand lacked, such as the relatively large domestic market and the proximity to Brazil, an even larger market. I’m still undecided, therefore, on whether domestic or global factors should be assigned more importance when explaining Argentina’s decline. My working hypothesis is that it was initially caused by the deterioration in the terms of trade and the frontier reaching its limits, but then made worse by political instability.

I am an independent scholar, so my opportunities for funding are limited. Any donation you can make to help me write The Poor Rich Nation would be fantastic.

I am a Chilean living in Chile. I am married with and Argentinian and usually travel to see her family, so I am very familiar with their domestic dynamics and even from the perspective of another emerging country citizen the things that happened in that country were and still are absolutely baffling.

The level of systematic and brazen corruption at virtually every institutional lever of the three powers of government with minor and very slow consequences has for all intents and purposes made the rule of law inexistent if a political/kleptocratic imperative is in the way.

The size and quality of government spending is ludicrous, central and local governments are plagued with political appointees that in many cases don't even care about showing up to work. And literally more than half of the population receives some kind of government transfer (planes sociales).

The unions in the country are extremely powerful and frequently use violence and intimidation to get what they want; their bosses are millionaires (nobody knows how) and in practice govern their unions for life and sometimes even pass on the leadership to their sons (sindicato de choferes y camiones).

If you compare the evolution of other Latin American countries (not a very demanding peer group) from your decline starting point to today, you can see that something very specific affected Argentina. And I don't think that a lack of natural resources was ever the cause.

So obviously I think that domestic factors are much more important in explaining the decline of Argentina, and I don't think that is possible to explain the phenomenon of Milei in any other way.

Could one argue that 1946-47 prices were distorted due to Peron’s agricultural policies, which would make the pre-1930 economy smaller when you extrapolate backwards?