Argentina/United States and Argentina/Australia updates

More on my revisions of Argentina’s historical GDP statistics

I have made some further revisions to my estimates of Argentina’s GDP statistics at purchasing power parity (PPP). The key difference is that I have used Colin Clark’s estimates of price levels of 1946–1947, then extrapolated back from there (see The Conditions of Economic Progress, 3rd ed., 1960, p. 37).

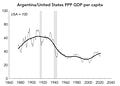

The results change the picture somewhat. Here you see Argentina’s current-price PPP GDP per capita relative to the United States’:

I have marked the two world wars, because I had previously pointed toward World War II as marking a break in Argentina’s relative wealth. In this version, by contrast, the relative decline really occurred from the 1930s to the 1960s, and then a little more in the 1980s and 1990s, with the trough coming during the crisis of 2001–2002.

In comparison with Australia, meanwhile, Argentina declined fairly unremittingly from the 1930s through to 2001–2002:

This comparison is particularly important because both countries prospered from exporting primary commodities in the twentieth century. It suggests, therefore, that Argentina’s domestic institutions played an important role in its relative decline. Although, notably, Australia had a lot of mineral resources that Argentina didn’t. Therefore, I am also going to work on New Zealand’s GDP per capita because it had similar institutions to Australia but, like Argentina, was far more dependent on agricultural exports.

If Argentina’s domestic institutions were to blame, these revisions of the GDP statistics point toward the 1930s as the decade when things began to go wrong. Most obviously, Argentina’s democratization was interrupted by the military coup of 1930. On top of that, the federal government began to monetize the public debt. As my sometime co-author, Carlos Newland, explains, it launched a “Patriot Loan”, to cover the fiscal deficit, even running a tango competition to advertise it:

The marketing efforts failed, however, and the federal government ended up printing money to purchase its own bonds. Correlation does not equal causation, of course, but it is notable that Argentina’s money-printing habit began at the same time as its relative decline, at least according to these revised estimates.

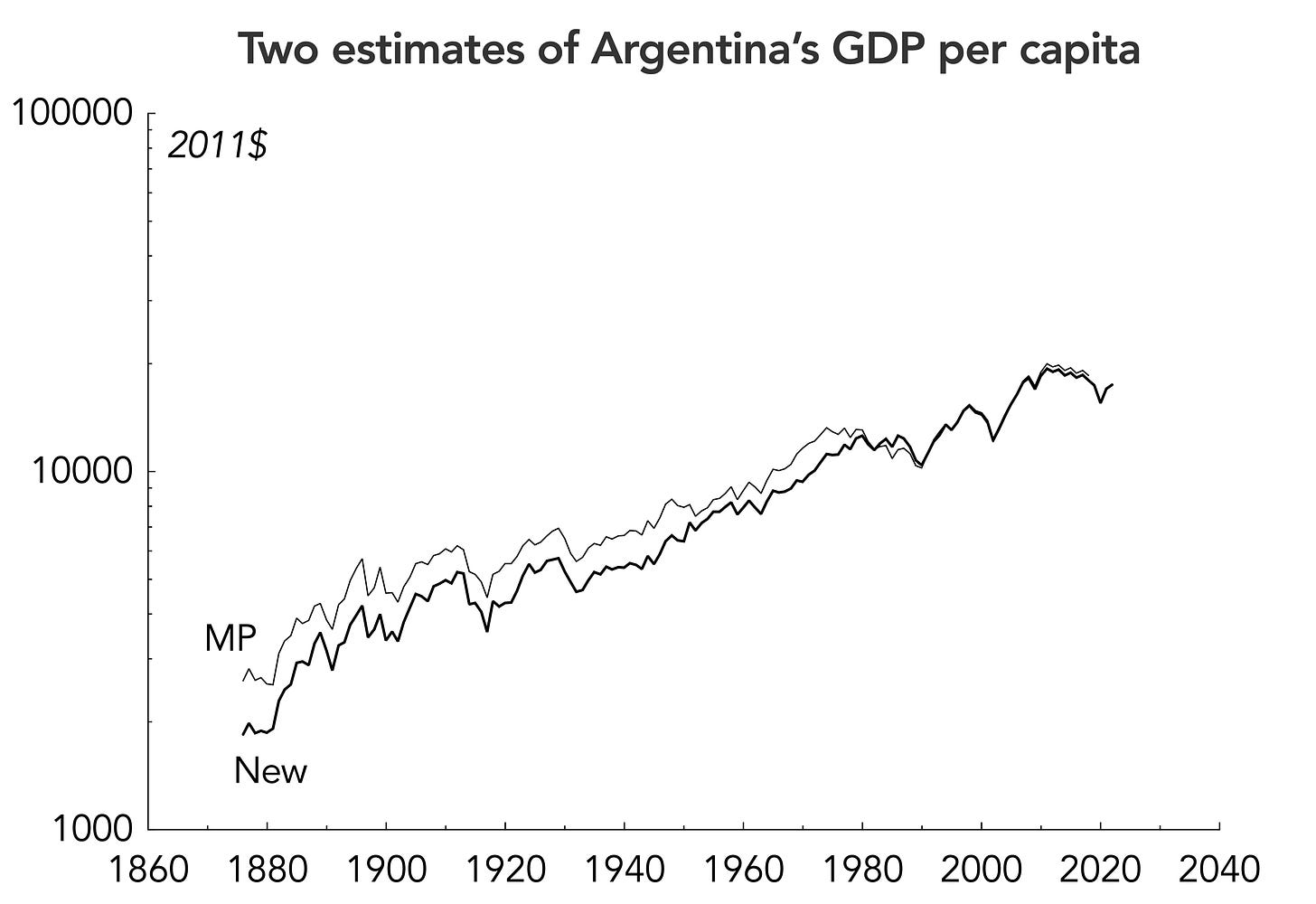

With these revisions, I have also made a first attempt to revise Argentina’s growth rate in constant prices by splicing a GDP deflator from the existing series. This is the result of my first attempt:

You can see that my revision shows somewhat faster growth than the most recent (2020) Maddison Project estimates. This finding should be expected because, as Leandro Prados de la Escosura has found, the standard splicing procedure used in Maddison Project-style estimates leads to a downward bias in the growth rates of developing countries experiencing structural transformation. Argentina’s twentieth century wasn’t quite as bad as is normally supposed.

The Economist, for example, claims that “Argentina’s real GDP per person was roughly the same in 2020 as it was in 1974”. Even the Maddison Project says that this is wrong: it shows Argentina’s GDP per capita growing by 21 percent over that period; for now, my revision suggests 49 percent. In 1974, my revised estimate shows Argentina’s current-price PPP GDP per capita at 36 percent of the United States’ and it fell to 33 percent in 2020.

The Economist article is a catalogue of negative tropes on Argentina. From reading it, you would have no idea that Argentina’s PPP GDP per capita had recovered considerably relative to both the United States and Australia since the crisis of 2001–2002. Indeed, the Economist even reminisces about the wonders of the macroeconomic policies that culminated in that crisis—it gushes about the “liberal government that managed to turn the country’s fortunes around for a decade”. In fact, my revisions suggest that the so-called “Convertibility” regime of a fixed exchange rate made Argentina descend to its lowest point since the late nineteenth century, in relative terms. It’s almost as if the Economist prioritizes liberal ideology over empirical reality. Who would have thunk it!

Only time will tell how sustainable Argentina’s recovery will be. I have also been catching up on the country’s recent history and I now have a better appreciation of the challenges it faces, both internal and external. But that will be the topic for another post.

I am an independent scholar, so my opportunities for funding are limited. Any donation you can make to help me write The Poor Rich Nation would be fantastic.

Could one argue that 1946-47 prices were distorted due to Peron’s agricultural policies? That would make the pre-1930 economy smaller since it was more dependent on farm exports.